Human Factors II

Case study: Epinephrine Autoinjector

FOREWORD

In medical device design and development, prioritizing "Efficiency" and "Safety" is crucial, drawing from years of experience conducting usability tests and documentation. Following the human factors, it's essential to comprehend the intended users and the use environment through comprehensive research. This holistic approach provides an objective perspective on how the user interface of the design supports the user's tasks efficiently and safely.

In this article, I'll simplify and discuss how human factors shape the early design research and conceptualization phase, using the Epinephrine autoinjector as an example.

WHAT IS AN EPINEPHRINE AUTOINJECTOR?

During severe allergic reactions, also known as anaphylaxis, administering epinephrine as emergency treatment is vital before professional medical intervention. Epinephrine, also called adrenaline, can reverse anaphylaxis symptoms, improving the patient's survival chances.

The Epinephrine autoinjector assists patients in injecting epinephrine for emergency treatment. Devices like the epinephrine syringes (epinephrine autoinjectors) are classified as Class II medical devices by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [1] and represent a moderate to high level of associated risk for the patient.

Note:

Regulatory classifications for medical devices may change over time and they can also be classified differently in different countries or regions.

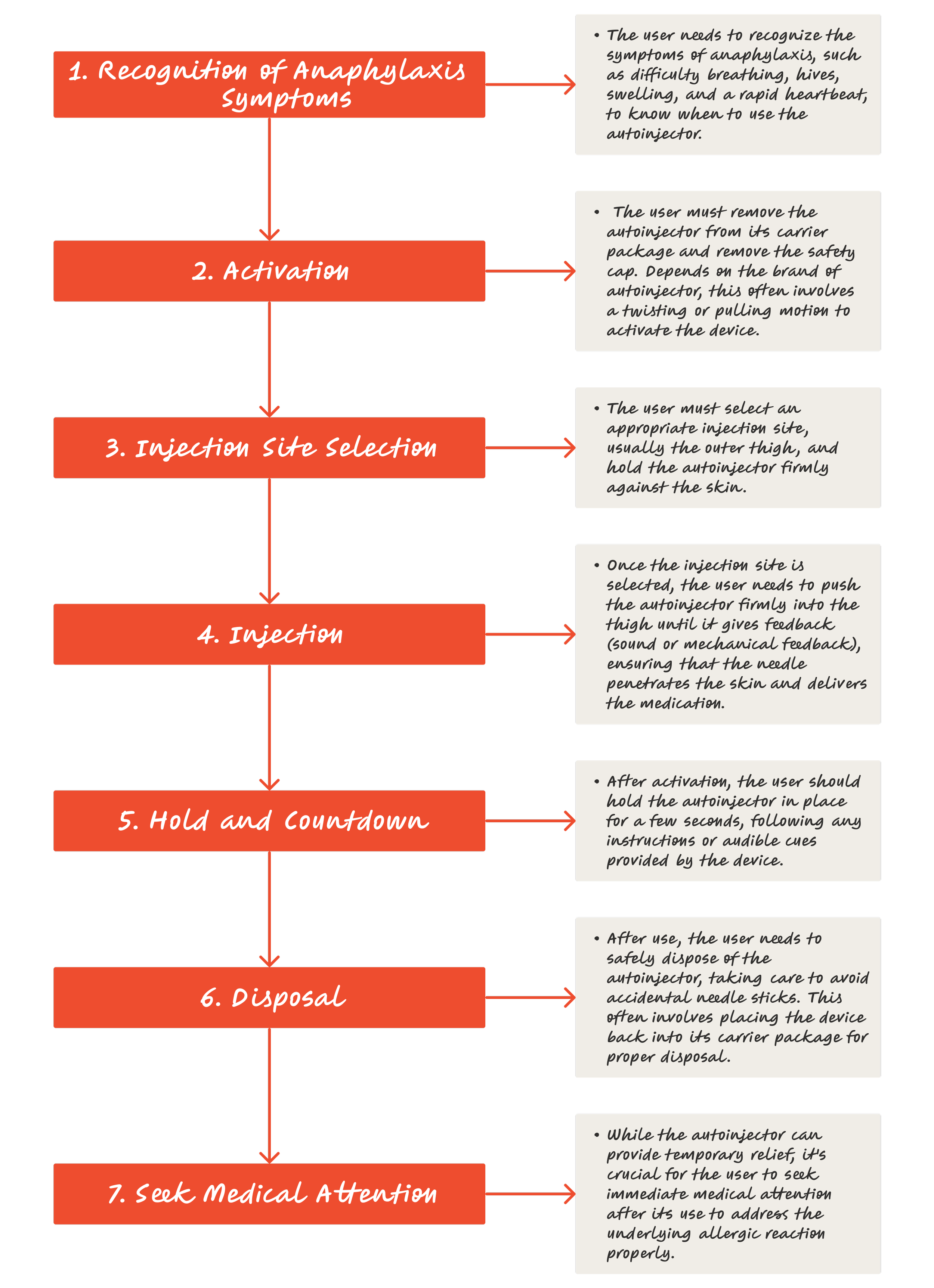

Before delving deeply into the case study of the Epinephrine Autoinjector, the user task flow below provides an overview of how patients treat severe allergic reactions with the device.

02. Retrieve the Epinephrine Autoinjector

03. Prepare the Autoinjector

04. Administer the Epinephrine

05. Seek Emergency Medical Assistance

06. Dispose of Used Autoinjector Safely

07. Replace the Epinephrine Autoinjector

CASE STUDY

Epinephrine Autoinjector

To initiate the discussion on Human Factors for Medical Device Design, I'd like to use the most common epinephrine autoinjector as an example.

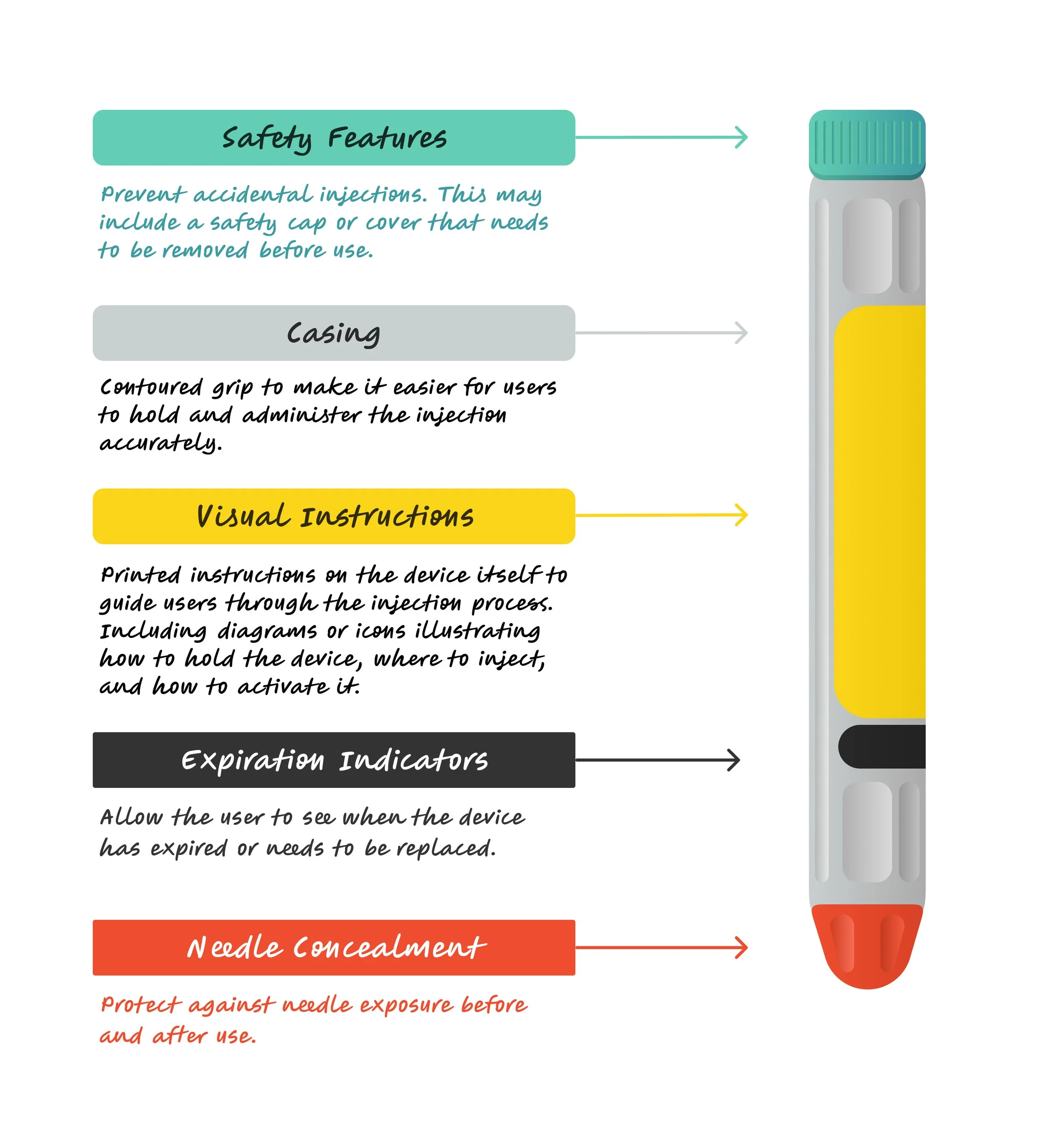

There are many different brands of epinephrine autoinjectors designed for the emergency treatment of severe allergic reactions or anaphylaxis. They deliver a pre-measured dose of adrenaline to counteract symptoms and enhance the person's survival chances during a life-threatening allergic reaction. Overall, most autoinjectors share common features such as needles, medications, safety mechanisms, visual instructions, and ergonomic design because they serve a similar purpose: to quickly and easily administer a dose of epinephrine in the event of a severe allergic reaction.

Image resource: https://www.owenmumford.com/en/drug-delivery/auto-injectors

Intended Users

Priority user group:

Individuals who have been prescribed Epinephrine to treat severe allergic reactions, such as anaphylaxis.

Caregivers who have been trained to take care of the people who have been prescribed Epinephrine.

When analyzing the intended users of autoinjectors, understanding the characteristics of primary users is essential. A holistic analysis of these characteristics significantly supports designers in understanding the user's physical and psychological capacity, ultimately enhancing the device's user experience. Generally, factors to consider include:

-

Children, teenagers, and adults at risk of severe allergic reactions. The age range can vary.

-

Male or female

-

No specific requirements, but users should be able to read and understand instructions for proper administration.

-

Users may have diverse educational backgrounds, emphasizing the importance of thorough education on recognizing allergic reactions and using the device correctly.

-

Proper training on using the Epinephrine Autoinjector is crucial, ensuring users and caregivers understand its proper usage

-

Varies depending on individual risk factors, suggesting the design should ensure easy access at all times.

-

No specific mobility requirements, but a seated or lying position is recommended to prevent injury such as dizziness or fainting after administering the injection.

Intended User Environment

The intended use environment for an autoinjector includes any location where severe allergic reactions might occur, such as homes, schools, workplaces, and outdoor settings. The design of autoinjector focuses on portability and accessibility to ensure quick and effective use in emergencies.

The use environment for an autoinjector can be indoor or outdoor, presenting unpredictable conditions. Factors to consider during design include:

Patient Position While Administering the Autoinjector: consider the patient's position during administration, ensuring they are in a stable and comfortable position.

Noise Range: Varies from low to high (measured in decibels, dBA). Take into account if the device emits sound feedback.

Light Range: Varies from low to high (measured in lux). Consider if the device includes labels with user information, such as visual instructions or a display.

Temperature: Varies from low to high (measured in degrees Celsius or Fahrenheit). Consider if the device's components, particularly the medication, function within specific temperature ranges.

Distractions: Be mindful of potential distractions in both indoor and outdoor settings, such as driving, eating, exercising, or the presence of children.

Hygiene: Caregivers may require personal protective equipment to maintain hygiene standards during administration.

Clutter: Be aware of other medical devices or medications present during administration, such as antihistamines, inhalers, or additional medications.

User Interface

Epinephrine Autoinjector (Common user interface)

User Tasks

Analyzing user tasks is crucial for medical design, aiding in creating user-centric solutions and identifying user requirements. Understanding tasks helps optimize workflow and identify potential user errors, which significantly leads to better solutions. For the autoinjector, I've listed two use models with their respective tasks:

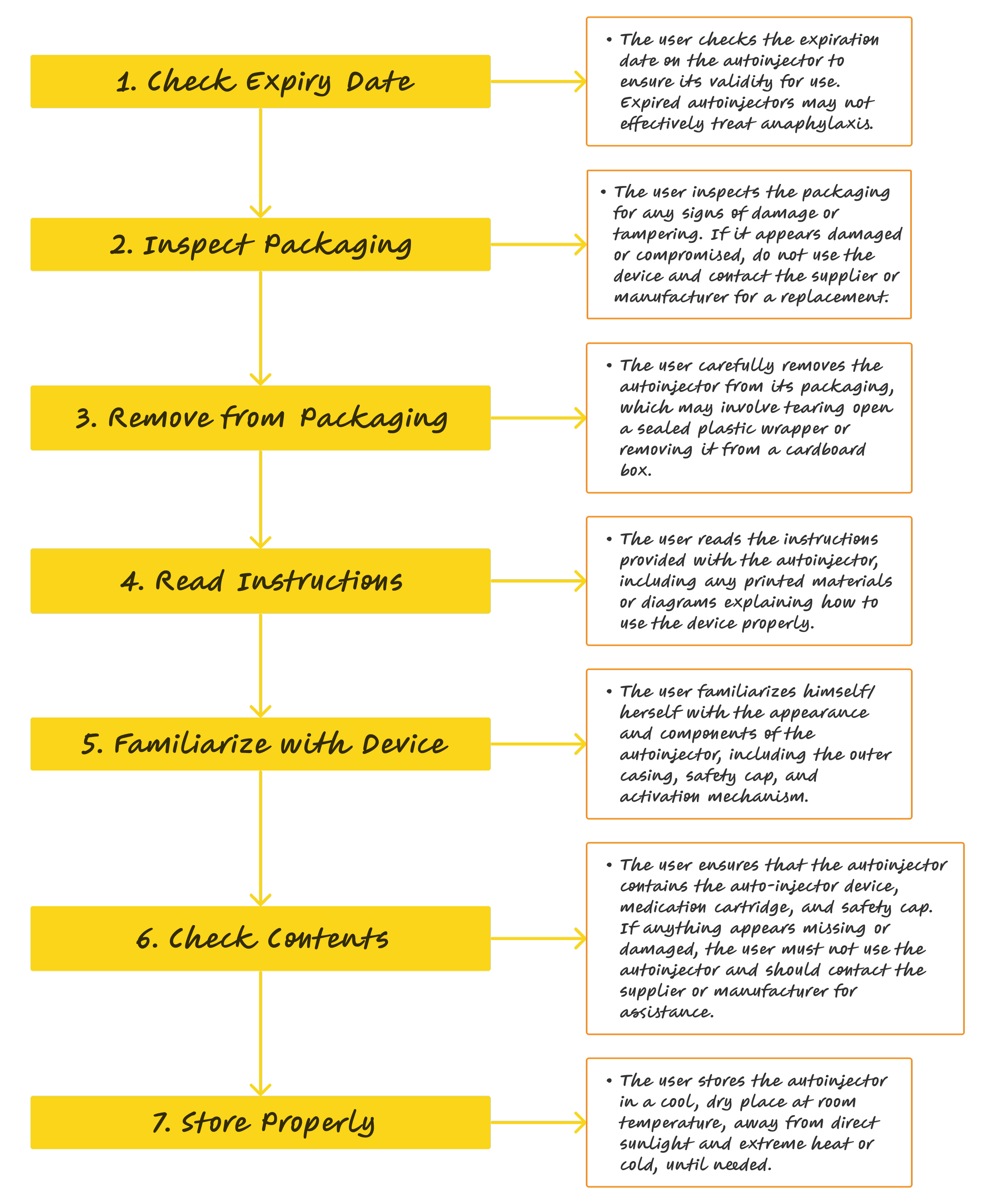

Unpacking

Clinical treatment

Use model - Unpacking autoinjector

User model - Clincal treatment

Potential Use Errors & Mitigation

Understanding user tasks helps identify potential use errors and mitigate risks to enhance product safety. Keep in mind that from a human factors perspective, it is challenging to avoid any use errors during usability testing. Human behaviour is unpredictable, and having multiple use errors does not necessarily indicate usability failure. It depends on whether use errors pose serious harm to patients and users.

As a case study, I have listed some potential use errors for the clinical use of the common autoinjector:

-

The user administers the autoinjector incorrectly, such as not holding it firmly against the thigh or not pressing hard enough to activate the injection.

-

The user injects the autoinjector into an improper site, such as the buttocks, affecting the effectiveness of medication delivery.

-

The user forgets to remove the safety cover, leading to a delay in treatment or the inability to activate the device.

-

Users, particularly caregivers, may fail to recognize anaphylaxis symptoms, resulting in a delay in administering the autoinjector or failure to use it altogether.

-

The user does not check if the autoinjector is malfunctioning due to manufacturing defects, expiration, or improper storage once receiving the device, leading to inadequate or failed medication delivery.

-

The user disposes of the device improperly, leading to needle stick Injuries and environmental cross-contamination.

There are many ways to mitigate potential use errors, such as comprehensive training, intuitive use manuals, or solving potential risks through design. From a design perspective, an ease-of-use design solution is always preferable to relying solely on a user manual, especially during emergencies.

I have chosen two potential use errors above and discussed mitigation below:

01. Incorrect Injection Technique

The user administers the autoinjector incorrectly, such as not holding it firmly against the thigh or not pressing hard enough to activate the injection.

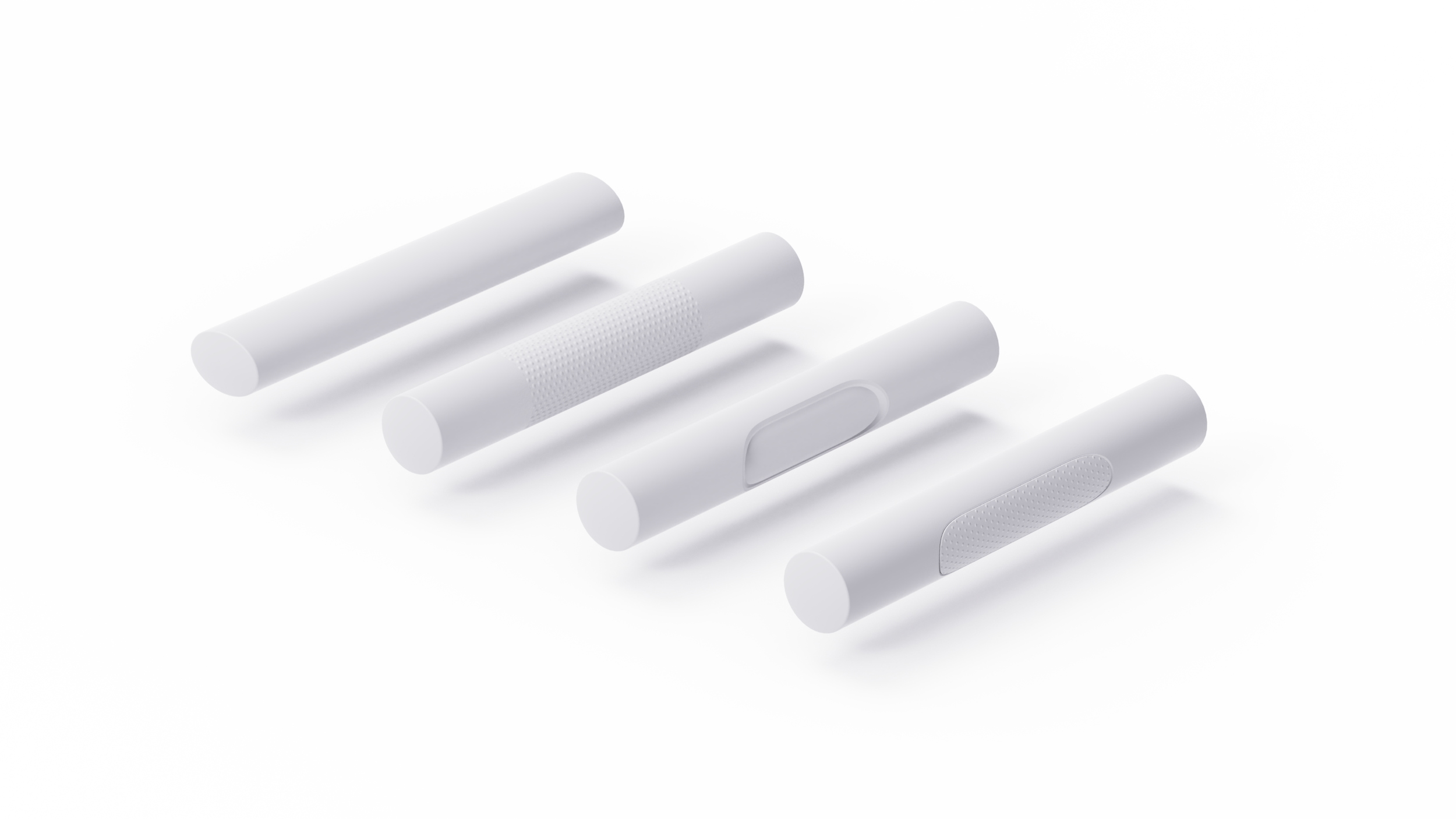

Rather than solely instructing users to firmly hold the autoinjector against the thigh, it is advisable to design the device casing to be easily grabbed.

Shapes such as ellipses can be grasped ergonomically (first tube), while considering texture with a specific pattern to increase friction can also make it easier to hold tightly (second tube). Sometimes, a sophisticated shape can also enhance grip, but it's important to consider factors like cleaning for reusable devices or manufacturing costs for complex surfaces (third tube). Another solution is to use different materials, such as rubber, in grasp areas to increase friction (fourth tube). There are many approaches to designing the shape that can significantly reduce the risk of such use error, particularly for users with limited grip strength.

02. Failure to Remove Safety Cover

The user forgets to remove the safety cover, leading to a delay in treatment or the inability to activate the device.

Analyzing its root cause can significantly aid in reevaluating the design. The user might not notice the safety cover because the design does not make it easily identifiable. Implementing colour-coded covers or providing step-by-step illustrations on the device, as commonly seen on many devices, could be a solution. Additionally, designing the cover for intuitive removal based on the user's instinctive habits could also be effective, as depicted in the image below:

When designing a safety cover, such as a safety cap, the cap must be very easy to remove, especially during emergencies. More importantly, the shape language should indicate that the cap is designed to be removed to activate the device. The vibrant and eye-catching "lemon yellow" ring indicates its use for urgency, with potential warning signals, and a clear instruction to pull it out by pulling the ring.

Overall, the two examples of mitigation I have discussed above are based on assumptions. It is always necessary to validate such assumptions with intended users. Furthermore, it is important to consider designing the medical device to be intuitive and safe at an early conceptual stage, rather than mitigating risks after validation by adding extra visual instructions or training materials, which can result in higher costs for medical device development and market access.

SUMMARY

In conclusion, I emphasize the critical role of human factors in designing medical device user interfaces, as illustrated by the Epinephrine autoinjector example. Understanding users, user tasks, environmental factors, and potential errors is key. By building on these factors, continually refining the concept can guarantee it's well-designed for users during validation.

References

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K160589